노인에서 흔히 보는 심장 초음파 소견

Abstract

As the world elderly population increases, it is critical to understand the cardiovascular changes during the normal aging process. Aging promotes cardiac structural and functional changes in the atria, ventricles, myocardium, valves, pericardium, and the cardiac conduction system, all of which echocardiography can reveal non-invasively. In this review, we outline common echocardiographic findings in the elderly, such as basal septal bulge, sclerotic aortic valves, diastolic dysfunction (relaxation abnormality, enlarged left atrium, and slightly increased tricuspid regurgitation velocity), and prominent pericardial fat. Understanding the common findings of the aging heart may help us to mitigate the escalating burden of cardiovascular diseases in the elderly.

Keywords: Aging; Heart; Echocardiography

중심 단어: 노화; 심장; 심장 초음파

서 론

국제 연합(United Nations)은 65세 이상 노인 인구 비율이 총 인구의 7% 이상을 차지할 때 고령화 사회(aging society), 14% 이상일때 고령 사회(aged society), 20% 이상일 때 초고령 사회(super-aged society)로 정의하고 있는데, 한국은 이미 고령 사회이며, 2027년이면 초고령 사회가 될 것으로 추정되고 있다[ 1]. 일반적으로 노인의 심장 모양은 교과서적인 젊은 표본 “정상 심장” 모양과는 약간 차이가 있는데, 교과서적인 “정상 심장”과 다르게 생겼다고 하여, 건강한 노인 심장을 “비정상 심장”이라 진단 내려야 할까? 물론 나이 자체를 질병으로 해석하는 견해도 있다. 나이가 들수록 고혈압, 관상동맥질환의 유병률이 증가 되는데, 다른 위험인자들을 보정한 뒤 나이 단독으로도 10년이 더 늘어날 때마다 심혈관 질환이 대략 두 배로 증가한다(60대 7.1%, 70대 13%, 80대 22.3%, 90대 32.5%) [ 2]. 그래서, 노인을 대상으로 대규모 전향적 연구를 진행할 때는 고민되는 부분이 있다. 과연 연구에 포함된 건강한 고령자가 정상적인 노화 변화를 가진 것인지, 질병과 연관된 변화를 가진 것인지 애매할 때가 있고, 20대의 심장을 가진 노인이 “정상”인 것인지 철학적인 물음이 던져지기도 한다. 그러나, 한 가지 분명한 것은 의사가 진료 행위를 함에 있어서, 정상적인 노화(normal aging)와 나이와 연관된 질환(age-related comorbidity)은 구별할 필요가 있다는 것이며, 노령에 따른 심혈관계 변화는 노인에서 흔히 동반되는 심혈관 질환과는 치료적 측면에서 확실히 구분되어야 한다. 때로는 임상에서 나이를 보정한 “정상” 참고치를 제시하기도 한다[ 3, 4]. 본 종설에서는 노화와 동반되는 심혈관계 구조 및 기능 변화를 파악하고, 특히 비침습적으로 심장을 관찰할 수 있는 심장 초음파 검사를 통해, 노인에서 흔한 심장 초음파 소견을 살펴보고자 한다.

본 론

노화와 동반된 심혈관계 변화가 일어나는 기전을 분자 또는 세포 수준에서 설명하는 연구들은 복잡하고 다양하다. 분자 경로에서는 자가포식(autophagy) 감소, 미토콘드리아 기능저하 또는 미토콘드리아에서 유래된 활성산소(reactive oxygen species) 증가가 주요하며[ 5], 이는 세포 수준에서 심근 세포의 소실, 세포 외 기질의 리모델링(extracellular matrix remodeling), 섬유화(fibrosis) 등의 변화로 표현된다[ 3, 6]. 이러한 정상적인 노화에 의한 심혈관계 변화는 잘 알려져 있는 다른 심혈관 질환 위험인자(고혈압, 당뇨병, 이상지질혈증, 흡연, 비만)를 동반할 때 가속화되어 질환으로 발현될 수 있다.

노화와 동반된 심혈관계 구조 및 기능 변화

첫째, 노화와 동반하여 심장 베타 수용체의 반응성이 감소된다[ 7]. 이는 심근혈류 증가가 요구되는 상황에서 심박수나 혈압이 증가되지 못하게 하고, 운동시 최대 심박수나 최대 심박출량은 감소시킨다. 그래서 최대 예상 심박수는 나이를 반영하여 설정된다(predicted maximal heart rate = 220 - age) [ 4]. 둘째, 노화와 동반하여 혈관과 심근이 경화된다. 나이가 듦에 따라 동맥과 정맥이 경화됨(stiffening)은 수축기 혈압 상승과 전부하(preload) 유지의 비효율을 초래하고, 노인 혈압의 특징인 맥압의 증가(pulse pressure widening)를 야기한다[ 8]. 심근벽은 후부하(afterload)의 증가로 비후될 수 있다[ 8, 9]. 경화된 심근으로 인해 이완기 순응도는 저하되면서 이완기 충만은 상대적으로 심방수축에 의존하게 된다. 그래서 노인에서는 심방세동처럼 심방수축이 없어지는 상황에서 심각한 이완기 충만 장애로 쉽게 이완기 심부전에 빠질 수 있다[ 10]. 셋째, 나이가 들면서 판막 및 심막이 퇴행으로 변한다[ 11]. 심장판막 중에서 특히 대동맥 판엽의 석회성 퇴행 변화가 대표적이다. 초기 발생 기전은 죽상경화증(atherosclerosis)과 관련되며 지질 침착, 염증, 석회화로 설명될 수 있다[ 12]. 또한 노인에서 흔히 관찰되는 심막의 지방 침착 및 섬유화는 노화에 따른 아로마타제 증가로 인한 지방세포 축척으로 설명된다[ 13]. 넷째, 나이가 들면서 자율신경계 반사가 저하된다[ 14]. 특히 압수용기반응(baroreceptor responsiveness)이 저하되면서, 노인에서 기립성 저혈압이 발생될 수 있다. 다섯째, 노화와 더불어 심장 전도계 이상 소견이 발생될 수 있다[ 15]. 동방 결절에 있는 박동을 만드는 세포 수의 감소 및 심장 전도계 전반에 걸친 섬유 지방 침착은 각종 전도 장애를 초래할 수 있다. 또한 좌심방 크기의 증가는 심방세동의 발생 및 유지와 밀접한 관계가 있다.

노인에서 흔한 심장 초음파 소견

서울 소재 한 종합병원에서 최근 15년 동안 시행한 심장 초음파 검사 건수에서 65세 이상의 노인 검사가 차지하는 비율은 34.9%였다(총 146,947건 중 65세 이상 51,258건[34.9%], 80세 이상 10,991건[7.5%], 90세 이상 926건[0.6%]이었다). 이와 같이 실제 임상에서 노인 심장 초음파를 많이 경험하고 있기 때문에, 노인에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 특징적인 심장 초음파 소견 및 주의사항을 노화 기전과 연결하여 숙지하는 것은 의미가 있다.

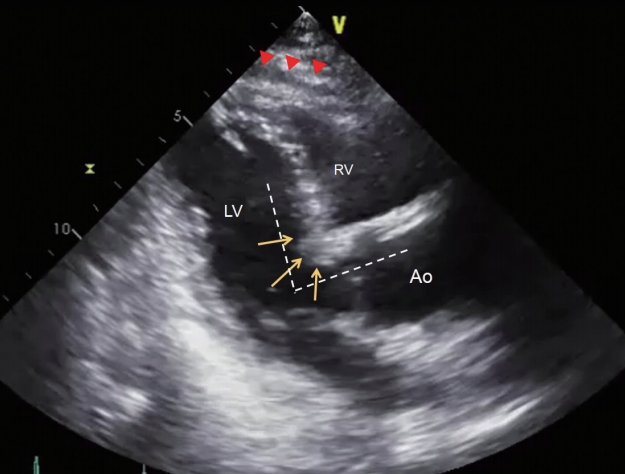

기저부 심실중격 돌출

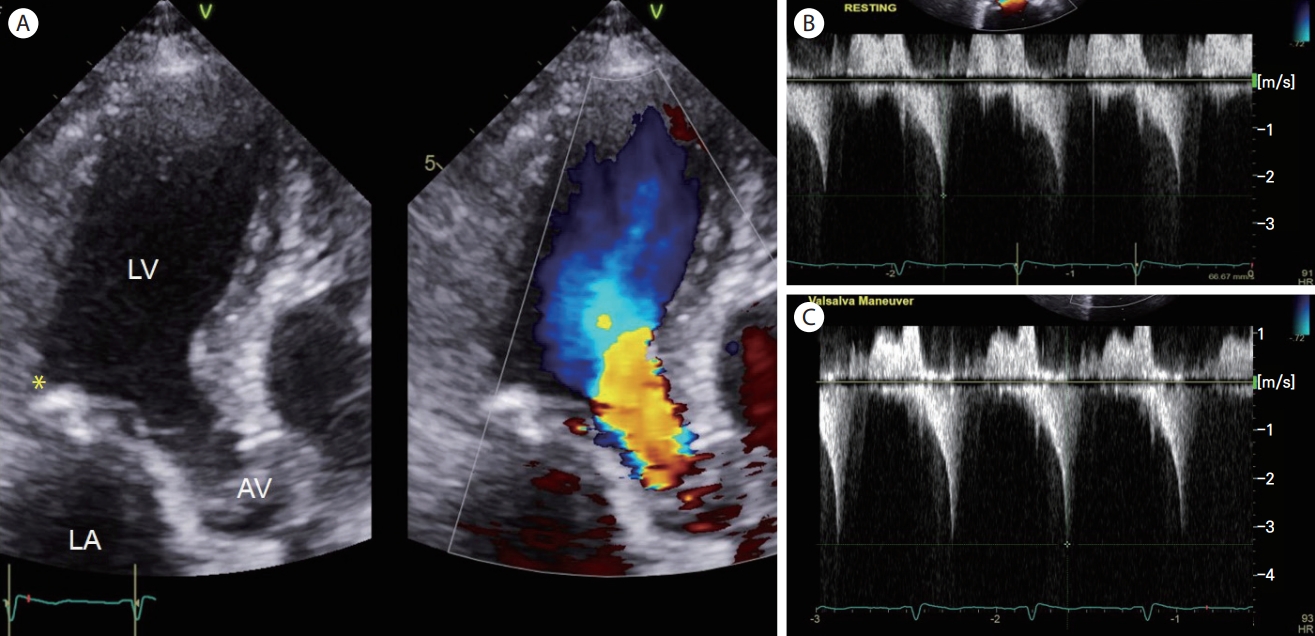

기저부 심실중격돌출(basal septal bulge)이란 초음파상 심실중격 기저부 두께가 중위부보다 2 mm 이상 두꺼운 경우를 말하는데, S자형 중격(sigmoid septum)이라 부르기도 한다. 유병률은 전체 인구에서는 1.5% 정도이나, 70대에서는 18% 정도로 높다[ 16]. 노인 심장 초음파에서는 이러한 기저부 심실중격 돌출과 동반하여 대동맥 근위부로의 이행각이 좁은 경향도 보인다( Fig. 1). 대부분은 혈역학적인 문제를 야기하지 않으며, 비후성 심근병증에서 볼 수 있는 의미 있는 좌심실 유출로 폐쇄(left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, LVOTO)를 동반하는 경우는 드물다. 그러나, 컬러도플러 영상에서 좌심실 유출로 수축기 혈류 속도 증강이 의심되면, 휴식 및 발살바 조작(Valsalva maneuver)을 통해서 최대 압력 차이를 측정하는 것이 추후 변화하는 상황에 대처하는 데 도움이 되겠다( Fig. 2). LVOTO는 도플러상 좌심실 유출로 압력차가 30 mm Hg 이상일 때를 말하는데(휴식 시뿐만 아니라 발살바, 기립, 운동과 같은 유발 시), 압력차가 50 mmHg 이상일 때 혈역학적으로 의미 있는 LVOTO라 할 수 있다[ 17]. 기저부 심실중격 돌출을 고혈압의 초기 심장 초음파 소견으로 보는 견해도 있기 때문에, 피검자의 고혈압 발생 여부를 주시할 필요가 있다[ 18].

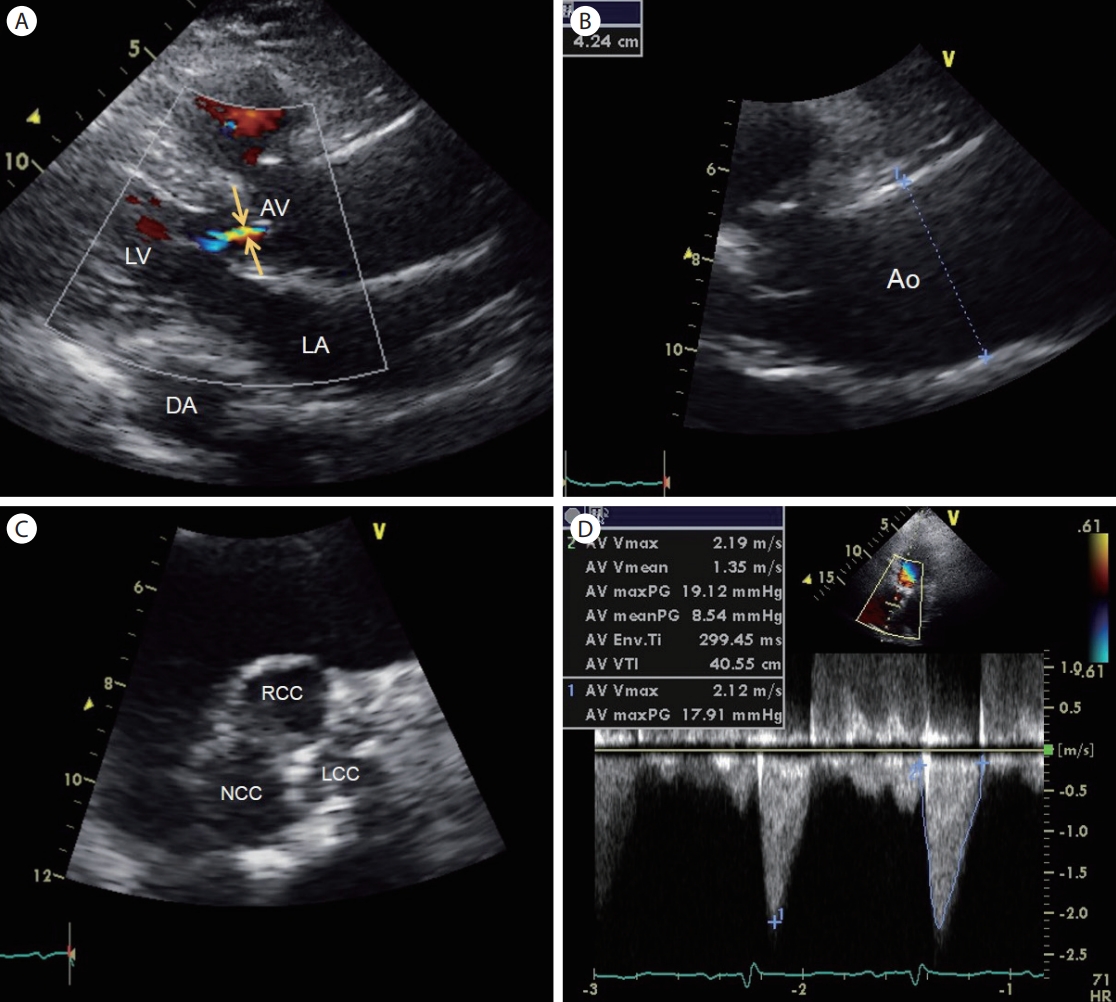

심장판막 퇴행성 변화

심장 초음파 검사상 대동맥 판엽의 비후 또는 석회화가 관찰되나, 혈역학적으로 판막의 협착을 동반하지는 않을 때(대동맥 판막 최대 혈류 속도 ≤2.5 m/s), 대동맥 판막 경화증(aortic valve sclerosis)이라 진단한다[ 19]. 대동맥 판막 경화증의 유병률은 나이가 들수록 증가되며, 75세 이상에서는 37% 이상이다[ 20]. 노인에서 특히 고혈압을 동반하고 있을 때, 대동맥 판막 경화증과 더불어 경한 대동맥 판막 역류증 및 대동맥 근위부 확장이 동반되어 있는 경우를 드물지 않게 발견할 수 있다( Fig. 3). 결국 임상적인 의미는 대동맥 판막 협착으로 이행되는 연속적인 스펙트럼에 놓여 있을 수 있다는 것인데, 심장 초음파를 통해서 혈류 속도 및 판구 면적, 좌심실벽의 비후 정도를 함께 평가하는 것이 도움이 된다[ 19]. 승모판막의 경우 나이가 들수록 승모판륜 석회화(mitral annular calcification)를 동반하는 경향을 보인다( Fig. 2). 승모판륜 석회화의 유병률은 70대 30%, 80대 이상은 60% 정도로 보고되어 있다[ 21]. 대부분은 노인이나 투석환자에서 심장 초음파 검사 중 우연히 발견되는데, 치료를 요하는 승모판 협착을 야기하는 경우는 드물다.

좌심실 이완기능 변화

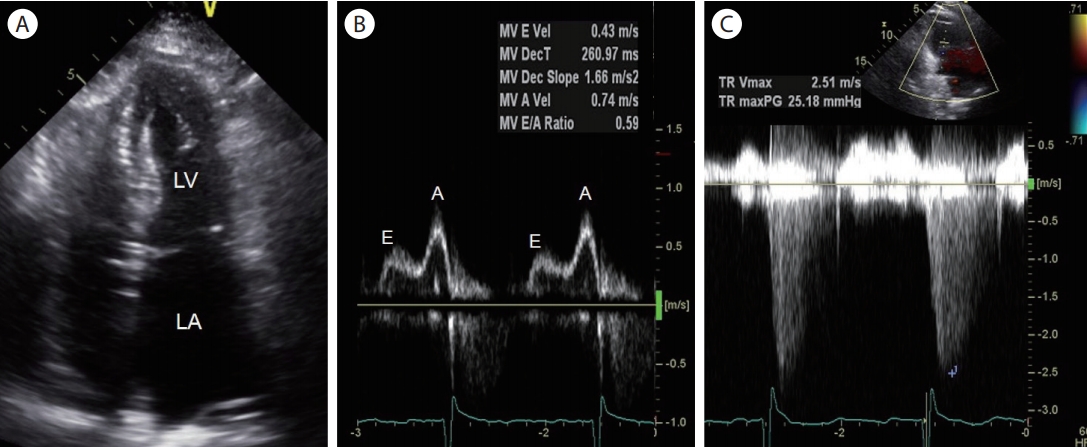

도플러 심장 초음파는 비침습적으로 심장의 이완기능을 평가하는 표준 검사법으로 잘 알려져 있으며, 이완기 심부전을 진단하는 지표로 쓰이고 있다. 이완기 심부전의 유병률은 나이에 따라 증가되는데, 50세 이상 15%, 50-70세 33%, 70세 이상에서는 50% 정도로 보고되어 있다[ 22]. 건강한 노령도 좌심실 이완기능의 변화를 보이는데, 좌심실이 경화되면서 도플러 초음파상 이완기 초기 충만 속도는 감소, 후기 충만 속도는 증가되는 1단계(grade 1 diastolic dysfunction)가 대표적이며, 좌심방의 크기는 커져 있어도 압력이 증가되어 있지 않기 때문에 대부분 심부전 증상은 없으며, 이는 임상적으로 치료를 요하는 심부전은 아니다( Fig. 4). 이완기능 평가에 있어서 2016년 발표된 미국 심장학회 가이드 라인(세 가지 주요 변수: average E/e’ >14, left atrial volume index >34 mL/m 2, tricuspid regurgitation velocity >2.8 m/s)을 따르고 있으며[ 23], 유럽 심장학회 가이드라인의 연령별로 구분된(20-40세, 40-60세, 60세 이상) 정상 이완기능 참고치도 주목할 만하다[ 3]. 고혈압도 없는 건강한 노령에서도 나이에 따라, 좌심방 크기 및 삼첨판 역류 속도가 증가됨이 보고되어 있다[ 24].

기능적 예비력 저하

노화는 인체 모든 시스템의 기능적 예비력(functional reserve)을 점차적으로 저하시킨다. 정상적인 노화와 동반되는 혈관 경화(vascular stiffening), 심실 이완기 순응도 저하, 자율신경 반사 저하 등의 심혈관계 변화는 노인에서 기능적 예비력을 저하시키는 원인이 되며, 이는 스트레스 상황에 대처하는 능력을 떨어뜨려, 갑작스러운 저혈압 또는 쇼크 등을 초래할 수 있다. 때문에, 노인에서는 정맥 마취 유도제[ 25, 26] 또는 심근을 저하시킬 수 있는 어떤 종류의 스트레스 노출 시라도 전후에 생체징후 모니터링에 각별한 주의를 기울여야 한다( Fig. 5).

결 론

이상으로 노화에 따른 심혈관계 구조 및 기능 변화의 기전과 심장 초음파에서 볼 수 있는 흔한 소견을 정리하였다. 고령 사회를 살아가는 의료인으로서 정상적인 노화에 따른 심혈관 변화를 이해하는 것은 필수불가결하다. 노화의 진행 스펙트럼을 이해한다면, 노인에서 받아들일 수 있는 정도의 심혈관 변화는 상호 간 충분히 설명될 수 있을 것이다. 그렇게 함으로써, 노화에 따른 변화를 질병으로 분류하여 노인이 건강 염려증에 빠지게 하는 것을 막고, 국가적으로도 지나친 의료비의 상승을 막으며, 조절 가능한 심혈관 위험인자를 관리하고 좋은 생활 습관과 운동을 권장하여 궁극적으로 건강한 노인 심장으로 이끌어가는데 도움이 될 수 있다. 또한, 정상적인 노화를 잘 알면, 노인에서의 병적인 심혈관 질환을 선별하여 진단과 치료의 목표 설정에도 도움이 된다. 덧붙여, 노인에서는 기능적 예비분이 적기 때문에 스트레스 상황에서 취약할 수 있다는 점도 늘 주의해야 한다. 본 종설에서는 노인에서 볼 수 있는 심장 이완기능 장애를 평가함에 있어 도플러 심장 초음파 기법을 주로 설명하였는데, 점차 활용도를 넓히고 있는 스트레인 초음파 기법도 심근 기능 저하를 조기에 진단하는 데에 기여할 것이라 사료된다[ 27].

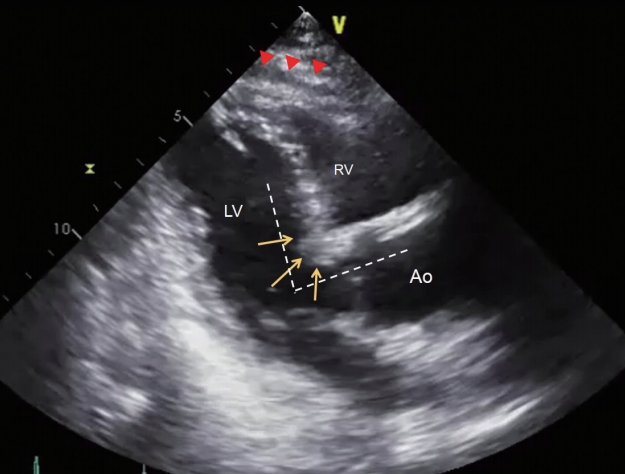

Figure 1.

Basal septal bulge in 109-year-old man. A 2D parasternal long-axis view reveals a prominent basal septal bulge (arrows), a narrow aorto-septal angle (dotted lines), and prominent pericardial fat (arrowheads). LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; Ao, aorta.

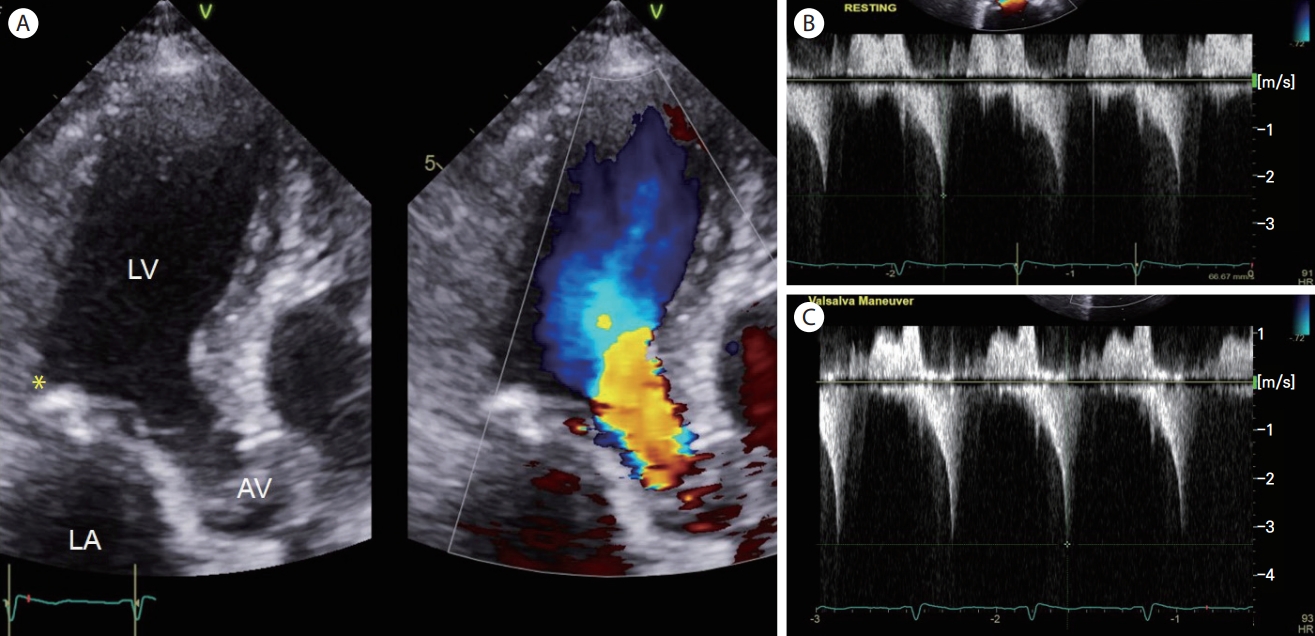

Figure 2.

Left ventricular outflow tract flow acceleration in 88-year-old woman. (A) Apical long-axis views of 2D and Color Doppler imaging show flow acceleration at the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT). Asterisk shows mitral annular calcification. Continuous-wave Doppler through the LVOT flow at rest (B) or during Valsalva maneuver (C) gives late peaking, dagger-shaped jets, slightly increased after Valsalva provocation (peak pressure gradient, from 23.7 mmHg to 44.9 mmHg). LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium; AV, aortic valve.

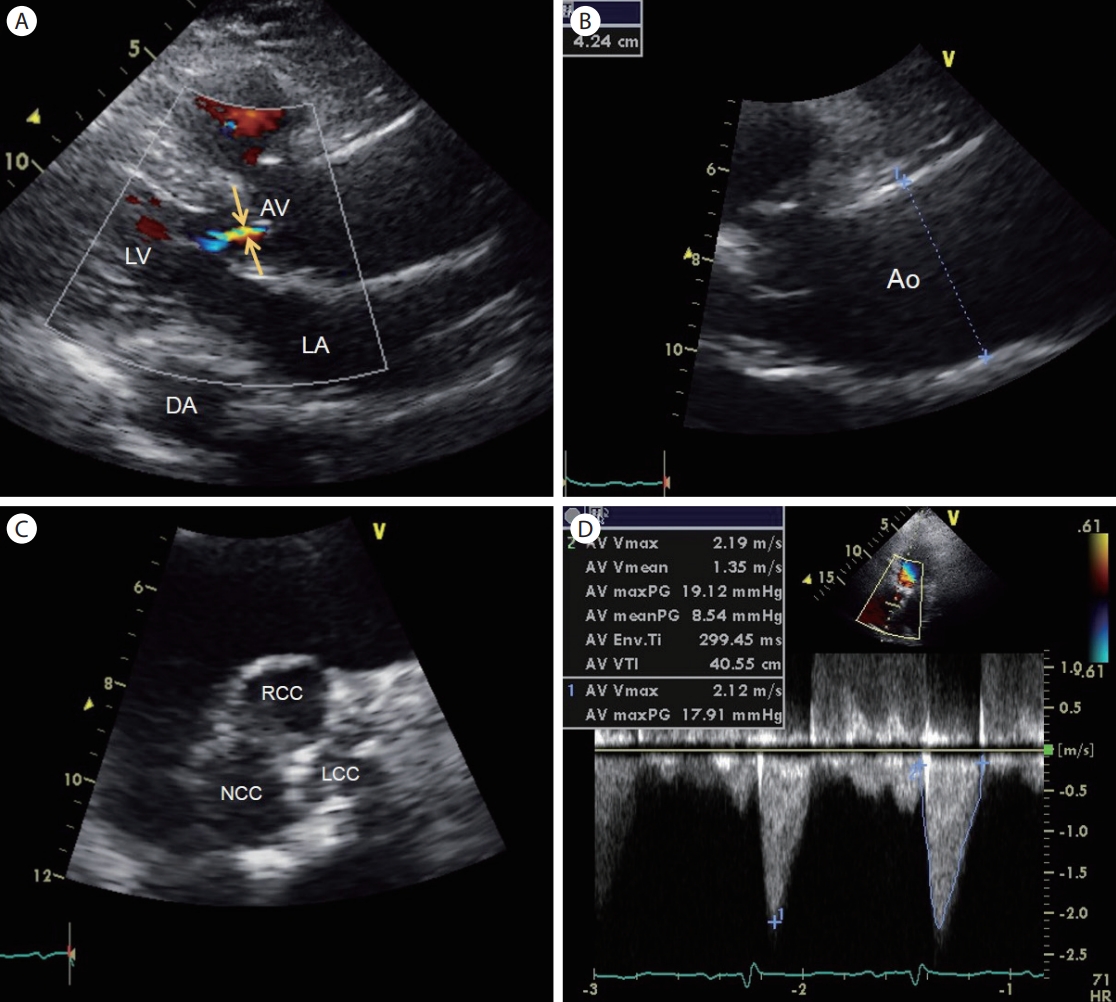

Figure 3.

Aortic valve sclerosis in 100-year-old woman with hypertension. (A, B) A parasternal long-axis view shows mild aortic regurgitation (arrows) and a slightly dilated ascending aorta (dotted line). (C) A parasternal short-axis view of the aortic valve shows thickened leaflets. (D) Continuous-wave Doppler through the aortic valve indicates a sclerotic aortic valve with a peak velocity of 2.1-2.2 m/s, without significant stenosis. AV, aortic valve; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium; DA, descending thoracic aorta; Ao, aortic root; RCC, right coronary cusp; LCC, left coronary cusp; NCC, non-coronary cusp; Vmax, maximum velocity; PG, pressure gradient.

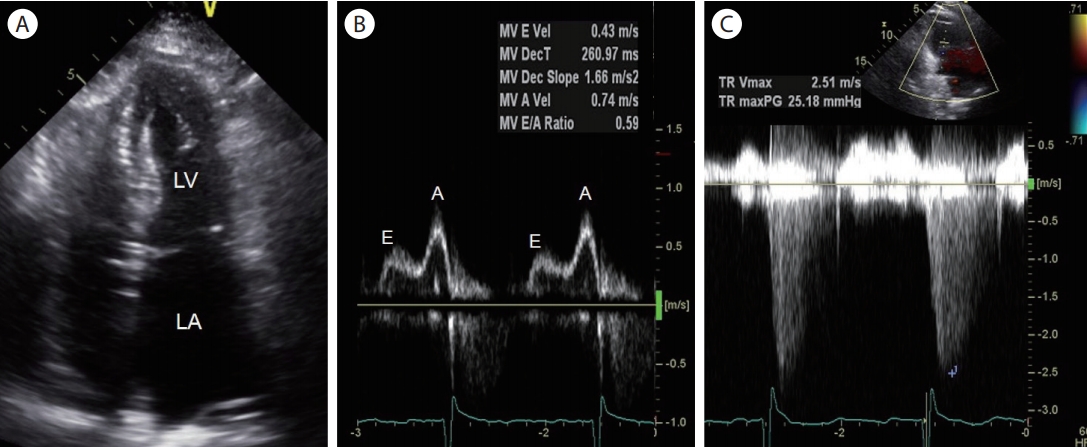

Figure 4.

Grade I diastolic dysfunction with normal left atrial pressure in 92-year-old man. (A) An apical 4-chamber view shows left atrial enlargement (left atrial volume index of 53 mL/m2). (B) Pulsed-wave Doppler mitral inflow velocity indicates grade I diastolic dysfunction (E/A ratio ≤0.8 + E velocity ≤50 cm/s). (C) No significant resting pulmonary hypertension is calculated from the tricuspid regurgitation maximum velocity. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; E, early ventricular filling velocity; A, late ventricular filling velocity; MV, mitral valve; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; Vmax, maximum velocity; PG, pressure gradient.

Figure 5.

Doppler Echocardiograms of 65-year-old woman undergoing propofol-based induction of anesthesia. Hemodynamic as well as echocardiographic monitoring is presented at baseline and 1, 3, and 5 minutes after intravenous propofol administration. (A) 2D echocardiogram, (B) Pulsedwave Doppler mitral inflow, (C) Tissue Doppler imaging of the septal mitral annulus, (D) Tissue Doppler imaging of the lateral mitral annulus. A “swan’s neck”-shaped reduction of systolic annular velocity is noted (arrows) along with a decline of systemic blood pressure after 1 minute, which is recovered after 5 minutes. BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; BIS, bispectral index.

REFERENCES

2. Savji N, Rockman CB, Skolnick AH, et al. Association between advanced age and vascular disease in different arterial territories: a population database of over 3.6 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1736–1743.   3. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–2200.   5. Lin R, Kerkelä R. Regulatory mechanisms of mitochondrial function and cardiac aging. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1359.   6. Wagner JUG, Dimmeler S. Cellular cross-talks in the diseased and aging heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2020;138:136–146.   8. Gates PE, Tanaka H, Graves J, Seals DR. Left ventricular structure and diastolic function with human ageing. Relation to habitual exercise and arterial stiffness. Eur Heart J 2003;24:2213–2220.   9. Olivetti G, Melissari M, Capasso JM, Anversa P. Cardiomyopathy of the aging human heart. Myocyte loss and reactive cellular hypertrophy. Circ Res 1991;68:1560–1568.   10. Bencivenga L, Komici K, Nocella P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in the elderly: a risk factor beyond stroke. Ageing Res Rev 2020;61:101092.   11. Kitzman DW, Scholz DG, Hagen PT, Ilstrup DM, Edwards WD. Age-related changes in normal human hearts during the first 10 decades of life. Part II (Maturity): a quantitative anatomic study of 765 specimens from subjects 20 to 99 years old. Mayo Clin Proc 1988;63:137–146.   12. Pawade TA, Newby DE, Dweck MR. Calcification in aortic stenosis: the skeleton key. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:561–577.  13. Bernasochi GB, Boon WC, Curl CL, et al. Pericardial adipose and aromatase: a new translational target for aging, obesity and arrhythmogenesis? J Mol Cell Cardiol 2017;111:96–101.   14. Huang CC, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, Weigand SD, Low PA. Effect of age on adrenergic and vagal baroreflex sensitivity in normal subjects. Muscle Nerve 2007;36:637–642.   15. Jones SA, Boyett MR, Lancaster MK. Declining into failure: the age-dependent loss of the L-type calcium channel within the sinoatrial node. Circulation 2007;115:1183–1190.   16. Diaz T, Pencina MJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and prognosis of discrete upper septal thickening on echocardiography: the Framingham Heart Study. Echocardiography 2009;26:247–253.   17. Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2733–2779.  18. Gaudron PD, Liu D, Scholz F, et al. The septal bulge--an early echocardiographic sign in hypertensive heart disease. J Am Soc Hypertens 2016;10:70–80.   19. Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, et al. Recommendations on the echocardiographic assessment of aortic valve stenosis: a focused update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:372–392.  20. Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29:630–634.  21. Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1231–1243.   22. Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: part I. diagnosis, prognosis, and measurements of diastolic function. Circulation 2002;105:1387–1393.  23. Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:277–314.  24. Van de Veire NR, De Backer J, Ascoop AK, Middernacht B, Velghe A, Sutter JD. Echocardiographically estimated left ventricular end-diastolic and right ventricular systolic pressure in normotensive healthy individuals. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2006;22:633–641.   26. Yang HS, Song BG, Kim JY, Kim SN, Kim TY. Impact of propofol anesthesia induction on cardiac function in low-risk patients as measured by intraoperative Doppler tissue imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26:727–735.

|

|